-

Company

Product

ALUMINIUM MACHINES

PORTABLE MITER SAWS FOR ALUMINUM

PORTABLE COPY ROUTER MACHINES FOR ALUMINIUM

PORTABLE END MILLING MACHINES FOR ALUMINIUM

AUTOMATIC MITER SAWS FOR ALUMINIUM

COPY ROUTER MACHINES FOR ALUMINIUM

END MILLING MACHINES FOR ALUMINIUM

ALUMINUM CORNER CRIMPING MACHINE

DOUBLE MITRE SAWS FOR ALUMINIUM

AUTOMATIC SAWS FOR ALUMINIUM

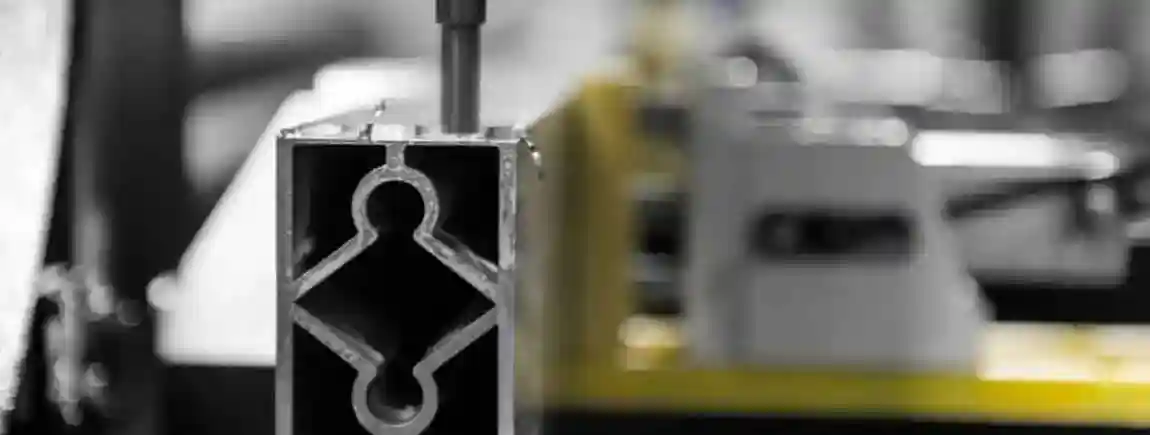

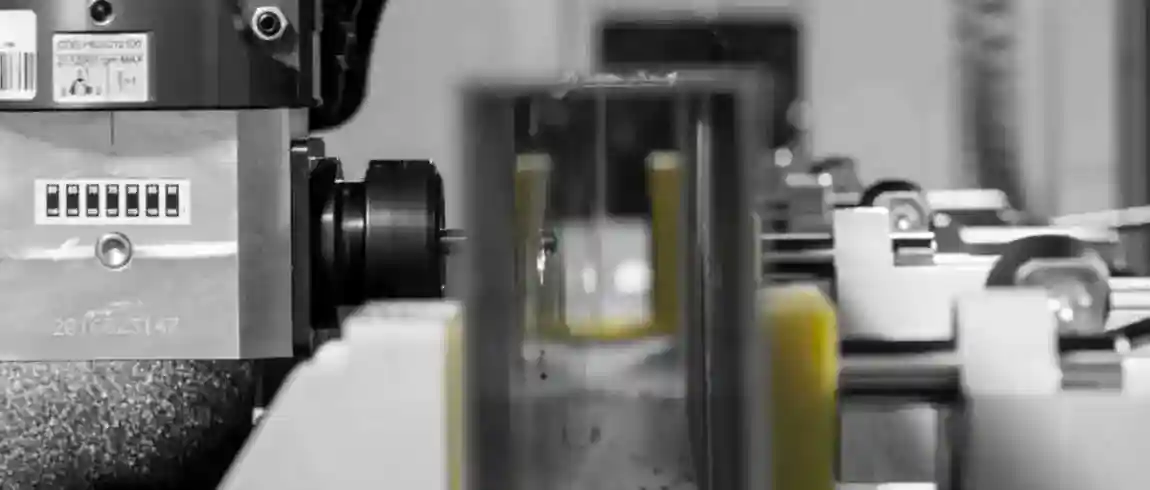

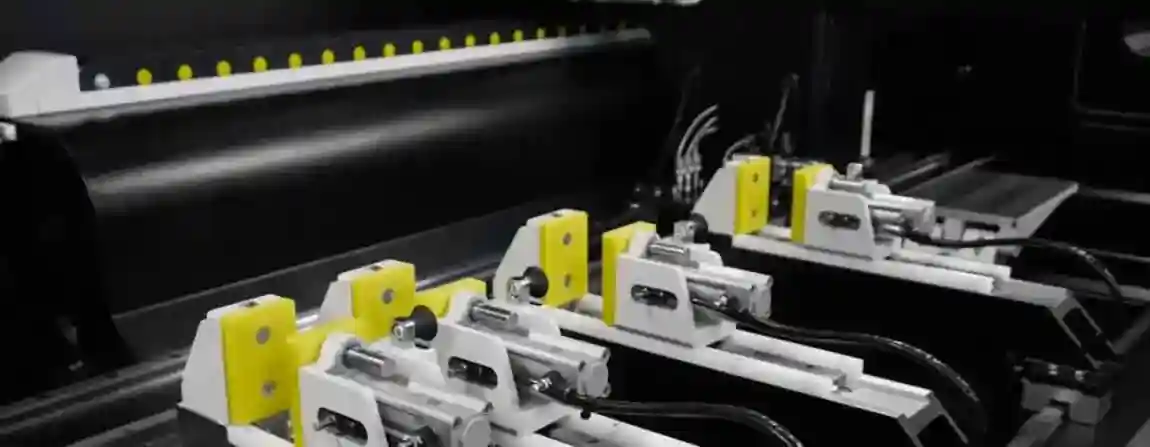

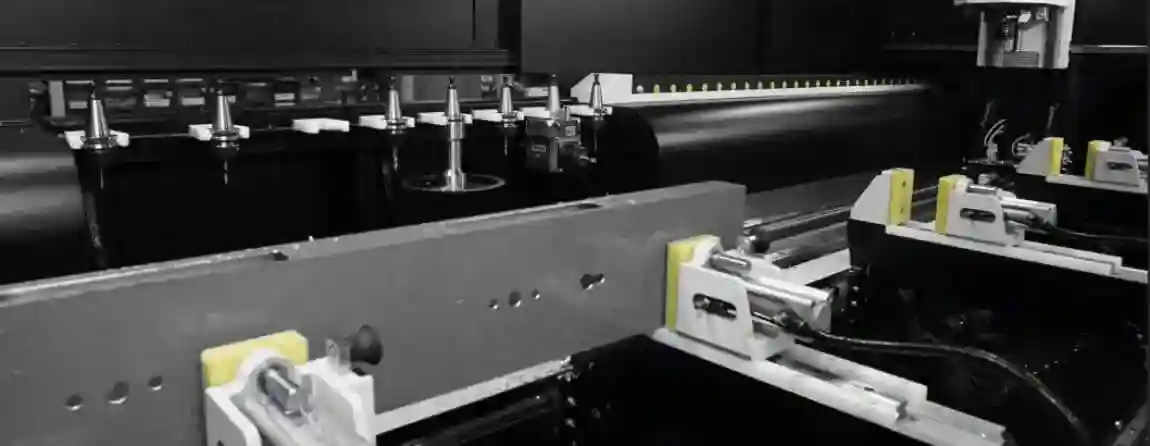

BAR PROCESSING CENTERS

MACHINING CENTERS FOR ALUMINIUM COMPOSITE PANELS

NOTCHING SAWS

WEDGE CUTTING SAWS AND NOTCH CUTTING SAWS

MITER SAWS FOR ALUMINIUM

PVC PLASTIC MACHINES

PORTABLE MITER SAWS FOR PLASTIC

PORTABLE COPY ROUTER MACHINES FOR PLASTIC

PORTABLE END MILLING MACHINES FOR PLASTIC

MITER SAWS FOR PLASTIC

COPY ROUTERS FOR PLASTIC

END MILLING MACHINES FOR PLASTIC

WELDING MACHINES FOR PLASTIC

CORNER CLEANING MACHINES FOR PLASTIC PROFILES

DOUBLE MITRE SAWS FOR PLASTIC

BAR PROCESSING CENTERS

GLAZING BEAD SAWS

AUTOMATIC MITRE SAWS FOR PLASTIC

METAL MACHINES

MANUAL METAL SHEET BENDING MACHINE

MANUAL BENDING MACHINES

HYDRAULIC BENDING MACHINES

NON MANDREL BENDERS

PLATE BENDING MACHINES

BORDERING AND TRIMMING MACHINES

HORIZONTAL PRESSES

BELT GRINDING MACHINES

PIPE NOTCHING MACHINES

PIPE POLISHING MACHINES

LASER CUTTING MACHINES

PRESS BRAKES

VERTICAL TURNING CENTERS

MACHINING CENTERS

WOOD MACHINES

GLASS MACHINES

ROBOTICS SPECIAL MACHINERY

Service

Blog

Contact

Blog

CAN YOU CUT ALUMINUM PROFILES WITH AN ANGLE GRINDER?

Can You Cut Aluminum Profiles with an Angle Grinder? An In-Depth Analysis of Technology, Risks, and Professional Alternatives

In workshops, on construction sites, and among ambitious DIY enthusiasts, one question arises with remarkable regularity: Can you cut aluminum profiles with an angle grinder? The answer to this question is not a simple yes or no, but a classic case of "it depends." Technically, it is possible to cut through an aluminum profile with an angle grinder. However, there is a vast gap between mere possibility and a professional, clean, precise, and, above all, safe method of working. Cutting aluminum profiles with an angle grinder is, in most cases, a last resort, a compromise associated with significant disadvantages and risks. This article will explore this topic in all its depth. We will analyze the functioning of the angle grinder and the physical properties of aluminum to understand why this pairing is so problematic. We will assess the risks in detail, describe the correct procedure for emergencies, and, most importantly, present the professional, safe, and qualitatively superior alternatives. The goal is to provide a well-founded knowledge that enables every user to make not just a possible, but the best possible decision for the respective task.

The Angle Grinder: Anatomy of a Powerhouse

To understand why cutting aluminum with an angle grinder is so tricky, we must first understand the tool itself. This power tool is one of the most versatile and powerful for the mobile processing of materials, especially metals and stone.

Historical Development: From the Stationary Grinder to the Mobile All-Rounder

The origins of the angle grinder lie in the stationary grinding machine. Since the beginning of industrialization, fast-rotating grinding wheels, driven by transmission belts or later by electric motors, were used for sharpening tools and deburring cast parts. The idea of making this principle mobile emerged in the early 20th century. The development of compact, powerful electric motors made it possible to put the grinding tool directly into the worker's hands. The first hand-held grinders were still large, heavy, and cumbersome. The decisive breakthrough was the development of the angle grinder in its current form, where an angle gear redirects the motor's rotation by 90 degrees. This allowed for a flat, ergonomic design and much better control. Originally designed for grinding and roughing work on steel, its range of applications has been steadily expanded through the development of various cutting and grinding discs, making it a seemingly universal tool.

Operating Principle: Abrasive Cutting through Material Removal

The core principle of the angle grinder is abrasive cutting. Unlike a saw, which uses geometrically defined cutting edges (teeth) to lift chips from the material, a cutting disc works with a huge number of irregularly shaped, extremely hard abrasive grains (e.g., corundum) held in a resin bond.

The high speed of the angle grinder (often over 10,000 RPM) accelerates these abrasive grains to an enormous velocity. Upon contact with the workpiece, each individual grain tears tiny particles from the surface. So, there is no machining in the classic sense, but rather a process of shattering and scraping away material. This process generates enormous friction and thus intense heat. The cut kerf is not created by a clean cut, but by literally grinding away material. This principle is highly effective for hard, brittle materials like steel, cast iron, or stone, but it is fundamentally unsuitable for soft, tough, and low-melting-point metals like aluminum.

Structure and Key Components

Every angle grinder, regardless of its size, shares the same basic structure:

-

Motor: A powerful electric motor (corded or cordless) designed for very high speeds.

-

Angle Gear: A robust gearbox that redirects the longitudinal rotation of the motor into a transverse rotation of the spindle.

-

Spindle: The shaft on which the cutting or grinding disc is mounted with a flange nut.

-

Safety Guard: One of the most important safety components. It partially covers the disc to protect the user from sparks and fragments of a bursting disc. It must always be mounted and correctly adjusted.

-

Handles: A main handle on the body and a side-mountable auxiliary handle allow for a secure two-handed grip on the device.

Aluminum Profiles: The Challenges for an Abrasive Cutting Method

Now let's look at the material. Aluminum profiles are widespread due to their lightness and stability. However, their physical properties make them a particularly unsuitable partner for the abrasive cutting principle of the angle grinder.

The Physical Properties of Aluminum Reconsidered

We know the properties of aluminum: soft, tough, low melting point, high thermal conductivity. In the context of a grinding disc rotating at over 10,000 RPM, these properties lead to a cascade of problems:

-

Low Melting Point (approx. 660°C / 1220°F): The immense frictional heat generated during abrasive cutting exceeds this point at the contact zone almost instantaneously. The aluminum not only melts, but partially vaporizes.

-

Softness and Toughness: Instead of being ground out as a small, solid particle, the aluminum becomes soft and sticky. It behaves like a tough chewing gum, not like a brittle cracker.

The Core Problem: Heat, Clogging, and the Consequences

Here lies the crux of the matter. The melted, sticky aluminum chip is not cleanly evacuated from the cut kerf. Instead, it immediately smears into the porous surface of the cutting disc. The spaces between the abrasive grains become clogged with aluminum. This is referred to as clogging or gumming up of the disc.

This triggers a devastating vicious cycle:

-

The clogged disc loses its abrasive effect. The sharp edges of the abrasive grains are covered with soft aluminum.

-

The disc begins to rub instead of cutting. The friction increases dramatically.

-

The temperature rises exponentially, leading to even more molten aluminum, which further clogs the disc.

-

The cutting progress slows down massively. The user tends to increase the pressure, which further increases friction and heat.

-

In the worst-case scenario, the clogged, overheated disc can lose its structural integrity due to extreme mechanical and thermal stresses and burst. This poses an extreme danger.

The Geometry of Profiles: Wall Thicknesses, Chambers, and the Danger of Snagging

Aluminum profiles are rarely solid. They usually consist of thin walls and several hollow chambers to achieve maximum stability with minimum weight. This geometry is particularly treacherous for the angle grinder. When transitioning from a thin wall to a hollow chamber and back to a wall, the cutting conditions change abruptly. The rotating disc can easily cant or snag on the edges of the webs. This leads to an uncontrolled kickback of the angle grinder, one of the most common causes of serious accidents with this device.

The Attempt in Practice: Cutting Aluminum Profiles with an Angle Grinder

If, despite all the disadvantages, the angle grinder is the only available option, strict rules must be followed to optimize the result and minimize the risks.

Choosing the Cutting Disc: The Decisive Factor

Using the right cutting disc is not just a matter of quality, but above all, of safety.

Standard Metal Cutting Discs (for Steel/Stainless Steel)

These discs are usually made of a corundum-based abrasive mixture. They are absolutely unsuitable for aluminum. They clog within seconds and become useless and dangerous. Their use is the most common mistake made when cutting aluminum with an angle grinder.

Special Discs for Non-Ferrous Metals / Aluminum

There are special cutting discs for non-ferrous metals like aluminum. These often use silicon carbide as the abrasive and have a softer bond. The softer bond ensures that the clogged abrasive grains break away faster, exposing new, sharp grains. This reduces clogging somewhat but does not solve the fundamental problem of heat generation. They are a better, but not a good, solution. The wear on these discs is extremely high.

Forbidden Attachments: Saw Blades on an Angle Grinder

Carbide-tipped saw blades or chainsaw-like attachments that can be mounted on an angle grinder are available on the market. Using such attachments to cut wood or metal is extremely dangerous and grossly negligent. An angle grinder has none of the safety features of a saw (riving knife, guard guide, brake function). The speed is far too high, and the danger of an uncontrollable kickback is immense. Countless severe accidents are attributable to this improper use. Our extensive practical experience from a multitude of customer installations sharpens our eye for such fundamental safety risks. That is why, during every inspection, we ensure that the tool-machine combinations used are not only efficient but are also operated in an absolutely safe and intended manner in accordance with CE conformity.

The Correct Procedure: Speed, Guidance, and Pressure

-

Speed: If the angle grinder has speed control, the lowest possible setting should be chosen to reduce frictional heat.

-

Guidance and Pressure: The device must always be held firmly and securely with both hands. Apply only minimal pressure! Let the weight of the machine do the work. A cut should be made in several short, engaging motions, not in one long pass.

-

Lubricant: Using a cutting wax stick or cutting oil can help. Dipping the rotating disc into the wax before the cut temporarily reduces friction and lessens clogging.

The Result: A Critical Evaluation of Precision and Surface Finish

Even with optimal procedure, the result is sobering:

-

Cut Surface: The edge is rough, often melted, and thermally discolored.

-

Burr Formation: a massive, sharp burr is created, which must be laboriously removed.

-

Precision: An exact, angularly correct cut (e.g., 90° or 45°) is practically impossible freehand. The cut kerf is wide and unclean.

The Risk Assessment: Why the Angle Grinder is Rarely the Best Choice

In summary, the disadvantages and risks can be divided into four main categories.

Extreme Burr Formation and Sharp Edges

The burr created by melting and displacement is not only unsightly but also extremely sharp and poses a significant risk of injury during further handling. The rework is time-consuming and costly.

Thermal Damage to the Material

The extreme heat exposure in the cutting zone can change the microstructure of the aluminum. Especially with hardened alloys, this can lead to a local loss of strength (annealing), which can be critical for statically loaded components.

Lack of Precision and Angular Accuracy

For constructions where profiles must be joined precisely and at the exact angle (e.g., frames, railings), the cut with an angle grinder is unusable. The resulting gaps are too large, and the connections are unstable and unsightly.

Health and Safety Risks for the User

-

Aluminum Dust: The fine, abrasive dust is respirable and harmful to health. A respirator is mandatory.

-

Sparks and Fire Hazard: Although aluminum does not produce sparks as intense as steel, the hot, glowing particles can ignite flammable materials in the vicinity.

-

High Noise Exposure: Angle grinders are among the loudest power tools. Hearing protection is essential.

-

Kickback Danger: Canting in the profile can cause the tool to kick back uncontrollably, leading to severe cutting injuries.

Professional and Safe Alternatives: How It's Done Right

Fortunately, there is a wide range of tools optimized for the clean and precise cutting of aluminum profiles.

For Mobile Precision: The Miter Saw for Aluminum

This is the top class for mobile or workshop-based cutting of profiles. A special metal miter saw (or a wood miter saw with the right blade) offers decisive advantages:

-

Clean Cut: A carbide-tipped saw blade with a negative tooth geometry machines the material instead of grinding it. The result is a smooth, low-burr cut surface.

-

Precise Angles: Miter cuts from 90° to 45° (or more) can be set exactly and repeatably.

-

Safety: Robust clamping devices fix the profile, and a safety guard securely covers the saw blade.

-

Speed: The actual cutting process is many times faster than with an angle grinder.

For Flexibility in Straight Cuts: The Hand-Held Circular Saw with a Guide Rail

For long, straight cuts, e.g., for ripping wide profiles or sheets, a hand-held circular saw with a special aluminum saw blade in combination with a guide rail is an excellent choice. It delivers high precision and good cut quality.

For Complex Shapes: The Jigsaw

For cutouts, radii, or non-linear cuts, the jigsaw with a suitable metal-cutting blade is the tool of choice. The speed is lower, but the flexibility is unsurpassed.

For Highest Productivity: Stationary Sawing Machines

In industrial manufacturing, specialized, stationary machines are used:

-

Up-Cut Saws: The saw blade comes from below, which optimizes safety and chip removal.

-

Double Miter Saws: Cut both ends of a profile simultaneously at the exact angle and to the exact length.

-

Band Saws: Ideal for cutting solid blocks or thick bundles of profiles.

Thanks to our wealth of experience built up over years, we know how crucial the selection and configuration of the right machine are for process reliability. Every inspection we conduct aims to ensure the highest quality standards and to certify the full CE conformity of the system.

A Head-to-Head Comparison: Angle Grinder vs. Miter Saw

| Criterion | Angle Grinder | Miter Saw for Aluminum |

| Cut Quality | Rough, melted, heavy burr | Smooth, clean, very low burr |

| Precision | Very low, freehand guided | Very high, angularly and longitudinally accurate |

| Safety | High risk (kickback, disc burst) | High (secure clamping, safety guard) |

| Speed | Very slow (effective cutting progress) | Very fast (cut in a few seconds) |

| Cost (Acquisition) | Low | Medium to high |

| Cost (Operation) | High (extreme disc wear) | Low (long service life of saw blades) |

| Health Impact | High (dust, noise, fumes) | Significantly lower (larger chips, less noise) |

| Application | Rough cutting, last resort | Precision cutting of profiles |

Conclusion: A Tool for Rough Work, Not for Precise Profile Cuts

We can now answer the initial question "Can you cut aluminum profiles with an angle grinder?" clearly and with nuance. Yes, it is mechanically possible. But it is, in almost every respect, the wrong method for this task. The angle grinder is a master of rough cutting and grinding of steel, but a bungler when it comes to the precise and clean cutting of aluminum profiles.

The physical properties of aluminum inevitably lead to poor cut quality, high tool wear, and significant safety risks. The result requires intensive rework and will never meet the requirements of a precise construction.

For anyone who regularly works with aluminum profiles, the investment in a suitable saw—first and foremost a miter saw with an appropriate saw blade—is not an option, but a necessity. The advantages in terms of quality, precision, speed, and above all, safety are so overwhelming that the angle grinder for this application should only be an absolute emergency and improvisation solution for a one-time, non-critical cut.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Which cutting disc must I use if I have absolutely no other choice but the angle grinder? If it is unavoidable, use exclusively a cutting disc that is explicitly designated for non-ferrous metals or aluminum. These typically have a softer bond and a different abrasive grain mixture (often silicon carbide), which delays the clogging of the disc somewhat. Never use a standard steel disc. Nevertheless, observe all mentioned safety instructions and do not expect a clean result.

Can I improve the cut quality by using wax or oil? Yes, that can help. Special cutting wax sticks intended for aluminum processing can reduce friction. Holding the rotating disc briefly into the wax stick before entering the material creates a lubricating film that reduces the adhesion of the aluminum. This slightly improves the process but does not solve the fundamental problems of lack of precision, heavy burr formation, and general safety risks.

Is a smaller, handier angle grinder safer for this task than a large one? A smaller device (e.g., for 115mm or 125mm discs) is easier to control than a large 230mm model. This can slightly reduce the risk of losing control during a minor cant. However, the fundamental risks—clogging and bursting of the disc, kickback when canting, and health hazards from dust and noise—remain the same. Safety primarily depends on the correct technique, the right disc, and personal protective equipment, not on the size of the device. The correct handling and maintenance of tools are crucial. Our expertise, based on servicing countless customer projects, ensures that we pay the utmost attention to compliance with quality and CE standards during acceptances and safety checks.

Request a free consultation www.evomatec.com

- Can you cut aluminum profiles with an angle grinder

- Cutting aluminum profiles with angle grinder

- Cutting aluminum

- Angle grinder for aluminum

- Cutting disc for aluminum

- Cutting aluminum without a saw

- Safety when grinding aluminum

- Burr formation aluminum

- Precision cut aluminum

- Miter saw for aluminum

- Alternative to angle grinder

- Cutting aluminum profile

- Cutting metal

- Aluminum melts when grinding

- Kickback with angle grinder

- CE compliant machine safety

- Professional aluminum cutting

- Tool for aluminum profiles

- Processing aluminum

GERMANY

GERMANY ENGLISH

ENGLISH FRANCE

FRANCE SPAIN

SPAIN PORTUGAL

PORTUGAL